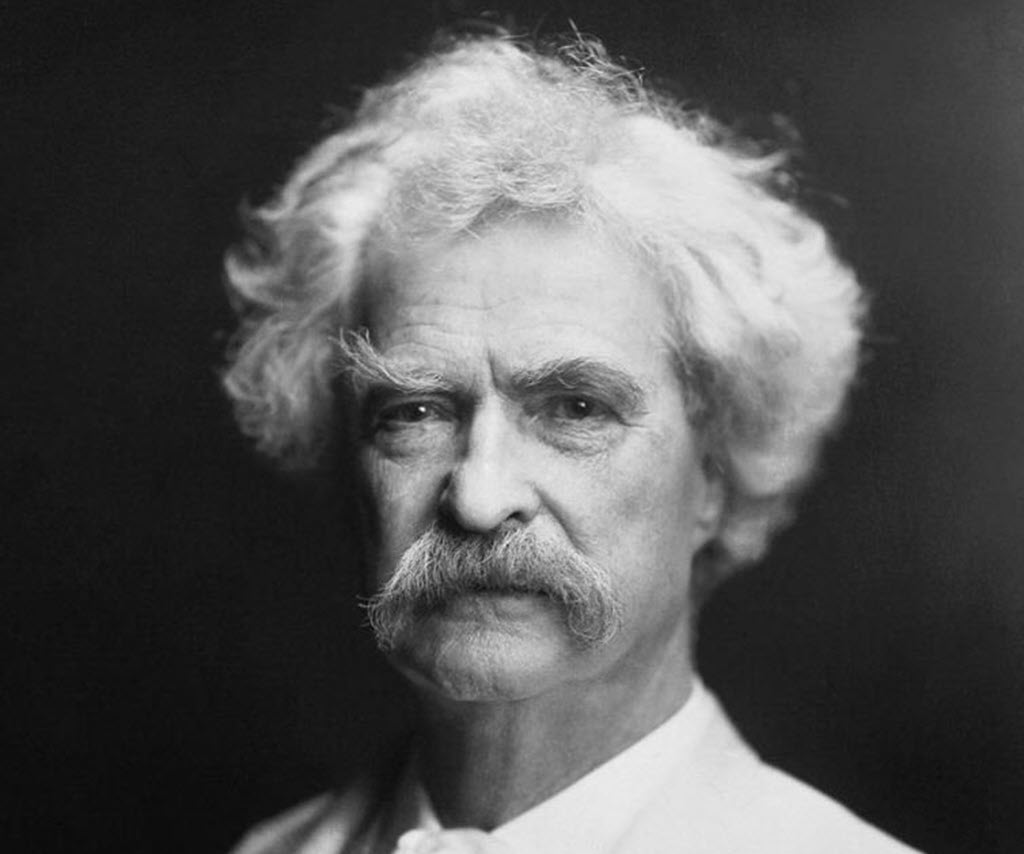

Mark Twain fled to Berlin in 1891 with his wife and three little daughters. He had earned a great deal of money from Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn and his other writing and lectures, but he invested in ventures that lost most of it and the family was short of funds.

So in the fall of 1891 Twain contacted his publisher about a quick scheme to generate cash: a translation of the most popular and best-known children’s book of the nineteenth century – a beloved book that could be found in almost every nursery in Europe and North America. Twain was sure his version would be a bestseller.

He completed his work by Christmas. His daughter Clara later recalled, “He had wrapped it up carefully, twining a huge red ribbon around it as an ornament. He seated himself near the tree and read the verses aloud in his inimitable, dramatic manner. He was a good actor! Jean and Susie and I were very youthful and susceptible. We responded almost with tears to Father’s graphic gestures.”

Alas, the book could not be published due to copyright issues. Twain filed bankruptcy three years later and his translation was shelved for 45 years.

Have you guessed what Mark Twain was working on? The undisputed champion children’s book in the 1800s, which continued to be published all over the world for the next hundred years?

I see you’ve guessed Alice In Wonderland. Good effort! You get points for participation. But no, it’s not our lovely Alice.

It’s a book of poems that my mom read to my sister and me our entire lives. They always made us laugh. Today they’re nearly forgotten.

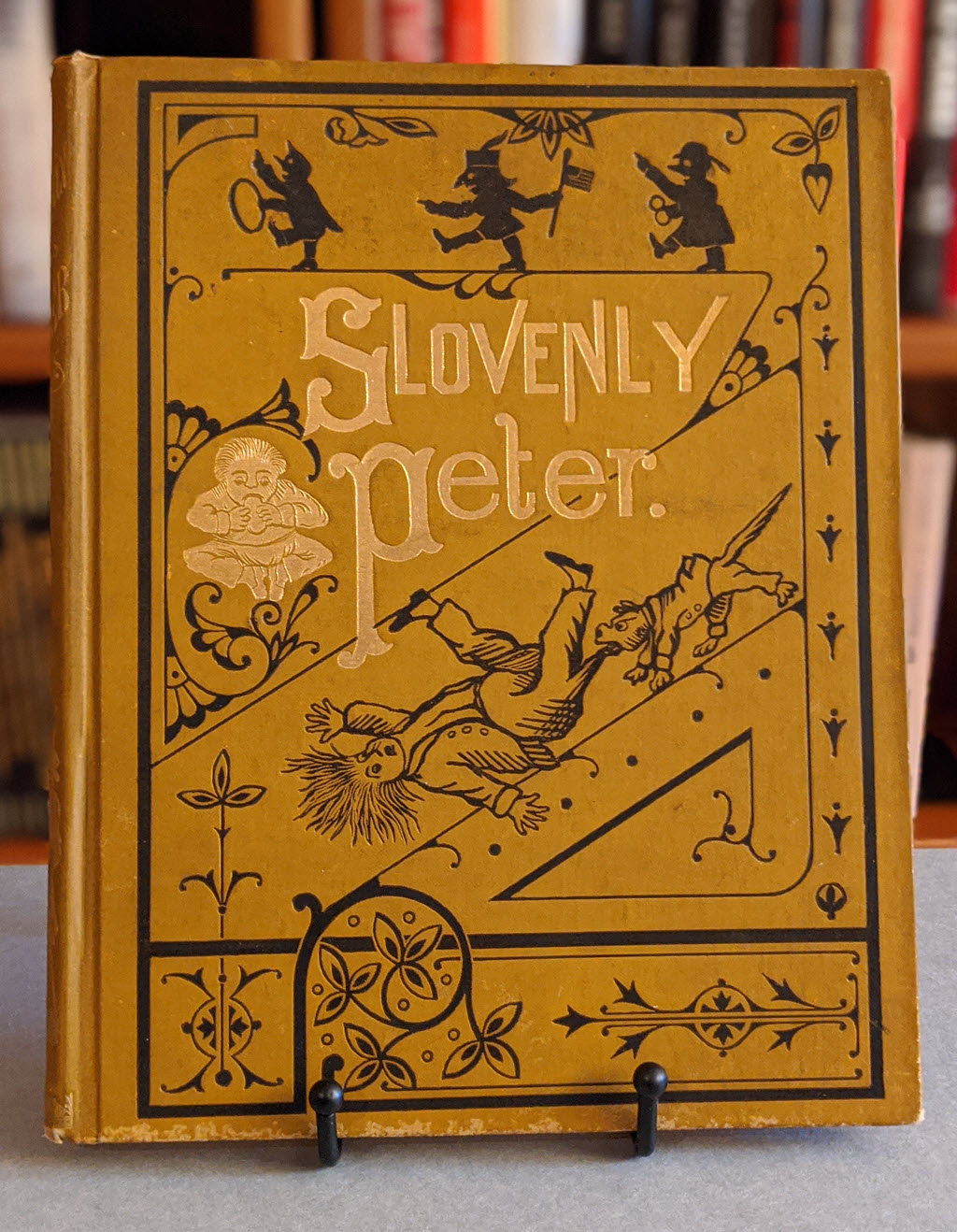

Welcome to the world of Slovenly Peter.

Slovenly Peter, or Cheerful Stories and Funny Pictures for Good Little Folks

Dr. Heinrich Hoffman was a physician who often made house calls on children. He developed a repertoire of rhymes and pictures to distract them during his visits. Friends pressed him to publish them. In 1845 the first edition of 1500 copies of the collection of poems – originally titled “Jolly Tales & Funny Pictures” – sold out immediately. Hundreds of authorized and unauthorized versions began to appear around the world.

Slovenly Peter (known over the years by several titles – Der Struwwelpeter, Shock-headed Peter, “Merry Stories & Funny Pictures”) is second only to the fairy tales from the Brothers Grimm as Germany’s greatest contribution to children’s literature. Hundreds of thousands of copies were in print in the US by the time the edition below was published in 1880.

Calling it “Cheerful Stories and Funny Pictures For Good Little Folks” is part of the joke. Hoffman’s poems are dark! They are cautionary tales with a twist, far different than standard Sunday School fare from the time.

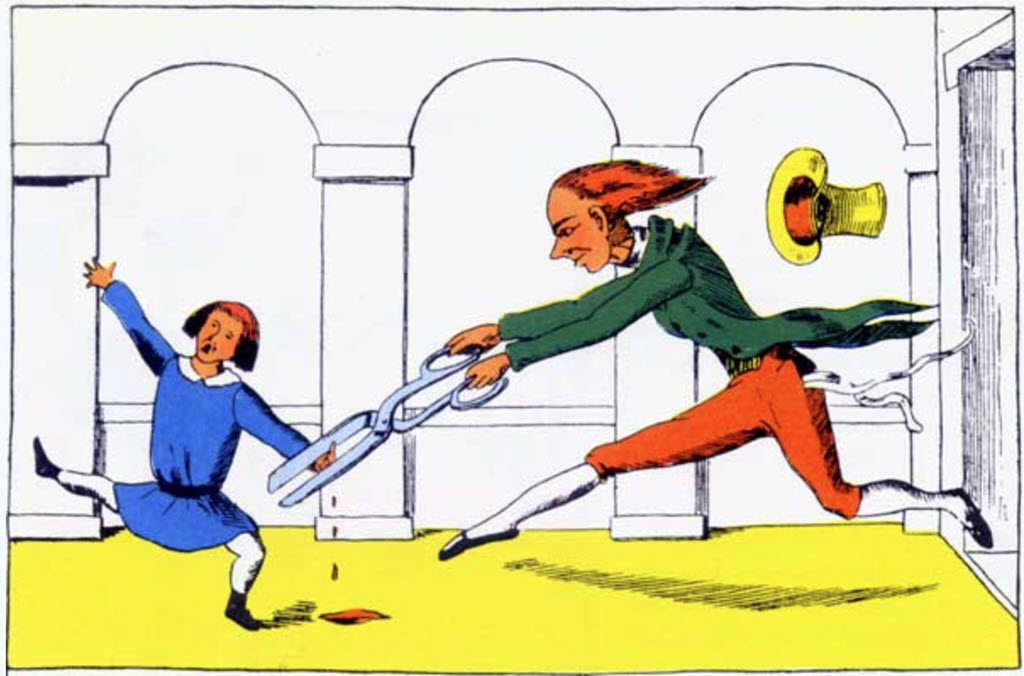

Take The Story of Little Suck-a-Thumb, for example.

Conrad’s mother warns him not to suck his thumb but he sticks his thumb in his mouth the minute she has gone.

A great long red-legged scissor-man bursts in and “Snip! Snap! Snip! The scissors go,” cutting off Conrad’s thumbs. Note the blood dripping on the floor, a nice touch.

“‘Ah,’ said Mamma, ‘I knew he’d come / To naughty little Suck-A-Thumb.’”

That’s the end. That’s all. Interesting fact: there are almost never any severed fingers in modern children’s literature.

This odd poem turns up over and over. Look at the pictures of Slovenly Peter and the tailor with his scissors. Merge them together in your mind and the resemblance to Edward Scissorhands is not accidental. The animated show Family Guy included this poem as a throwaway gag.

In The Dreadful Story of Harriet and the Matches, Harriet is told not to play with matches but she can’t resist because flames are so pretty.

She accidentally sets herself on fire and burns to death while her pet cats watch. Nothing is left except her little scarlet shoes among her ashes. The cats’ tears make a little pond.

Okay, I get it, these sound horrific when I describe them. Point taken.

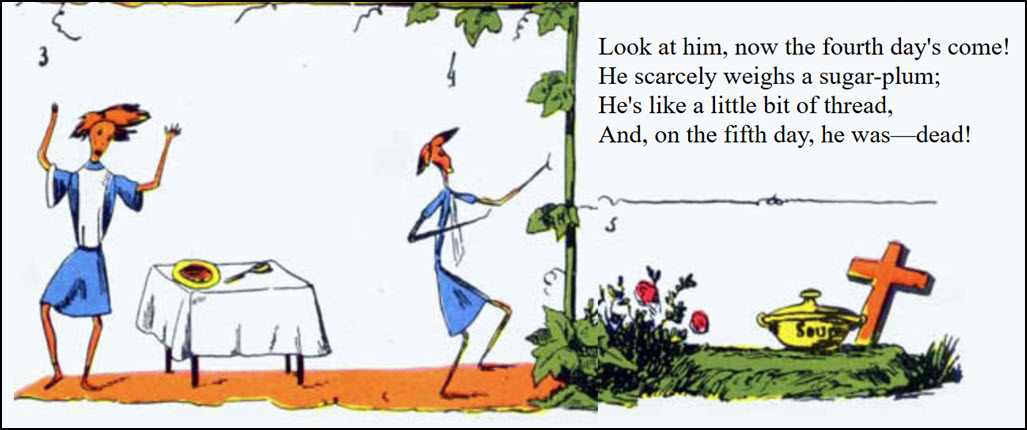

If I had to pick a favorite, it would be The Story of Augustus. “Augustus was a chubby lad.” My whole childhood comes back when I hear that line. Whenever my sister or I threatened to be fussy eaters, my mom would say “Augustus was a chubby lad,” and we would all laugh and look back with mock seriousness and declare firmly, “I will not eat my soup today.” Then we’d eat the damn lima beans or whatever was on the plate.

You see, one day Augustus cries, “O take the nasty soup away! I won’t have any soup today!”

He gets thinner, he wastes away, but still he cries, “Not any soup for me, I say. I WON’T have any soup today!”

The story has a dramatic ending.

“Look at him, now the fourth day’s come!

“He scarcely weighs a sugar-plum;

“He’s like a little bit of thread,

“And, on the fifth day, he was – dead!”

I can’t help my sense of humor. That picture of a stick figure, and the little grave, that is some hilarious stuff.

It’s also disturbing as hell, so there is no shortage of scholarly analyses of whether the poems are healthy for children. This paper cites papers from critics claiming that “Struwwelpeter has been frightening and horrifying children for generations” and that the poems “reflect a peculiar hostility to children.” There have been arguments about whether the books should be banned and whether the poems are disrespectful of people suffering from anorexia, or uncombable hair syndrome, or ADHD.

And it’s hard to argue. The poems are indefensible. Maybe I should blame Slovenly Peter (and my mother) for giving me a peculiar sense of humor that lets me enjoy Harold & Maude, Bad Santa, Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, and A Clockwork Orange. I raised my kids on Roald Dahl and Lemony Snicket books, which come from the same tradition.

Struwwelpeter turns up frequently in modern culture. The Scissorman is a character in Jasper Fforde’s novel The Fourth Bear. There have been stage productions, films, musical compositions, and comics inspired by Slovenly Peter. In 1941 Strewwelhitler was released, parodying Adolf Hitler. I just got a copy of Tricky Dick And His Pals, a book published in 1974 to mock the Nixon administration in the style of Struwwelpeter.

One more historical note: Slovenly Peter was one of the first children’s books with brightly colored pictures. It is credited as being a precursor of modern comic books.

What about Mark Twain’s translation of Slovenly Peter?

Sorry, I got distracted.

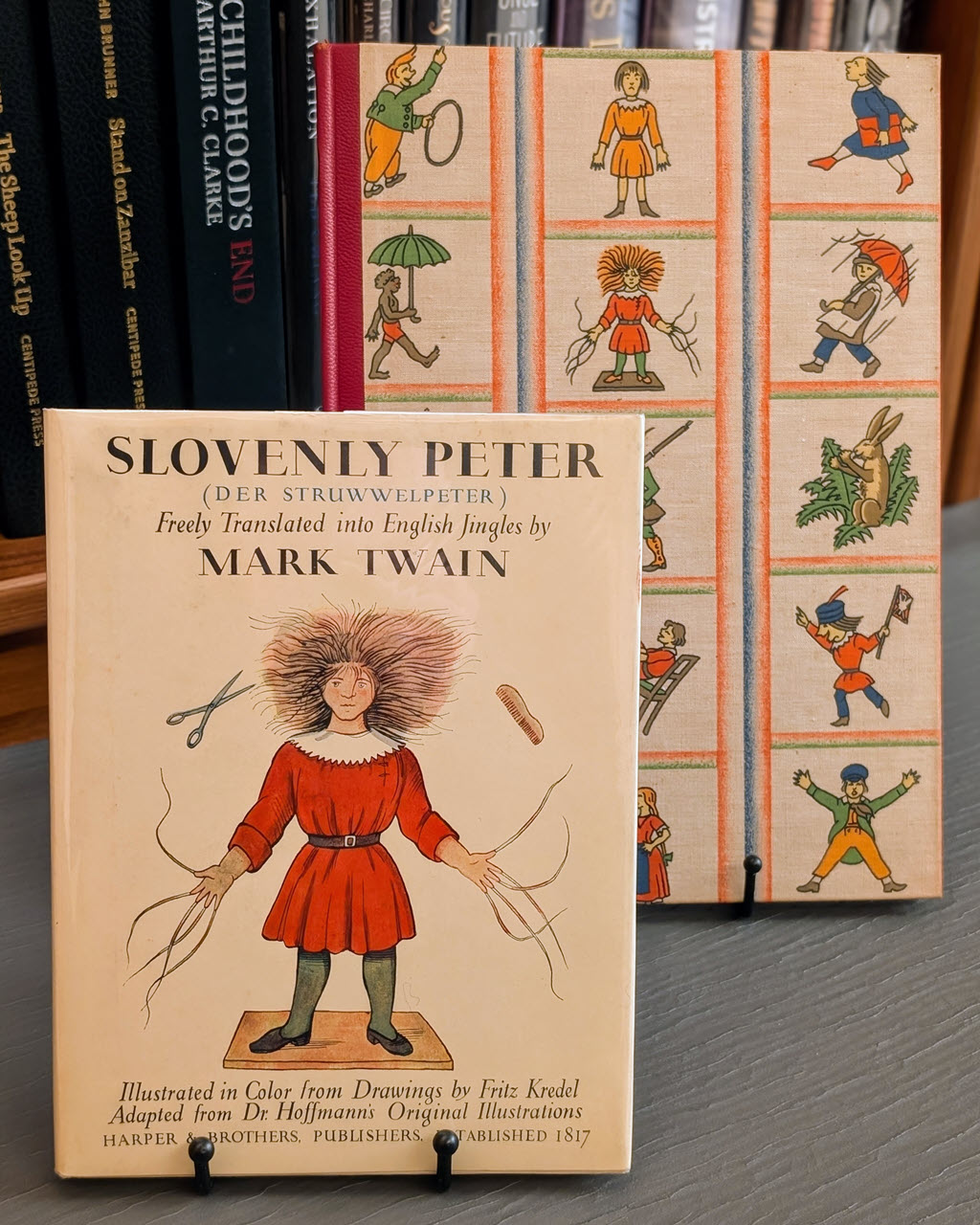

Mark Twain’s translation of Slovenly Peter was finally published in 1935, twenty-five years after his death. Limited Editions Club published 1500 numbered copies of an oversize version, shown in the rear in the above photo. The trade edition in front was published simultaneously. Clara Clemons wrote a foreword about Twain’s work on the translation and the family Christmas. It’s still in print in hardcover from Dover Books.

Twain described his versions of the poems as “freely translated,” emphasizing humor and violence left out of other English translations. His translations are inaccurate and generally awkward, but he captures the spirit of the German originals perhaps more closely than the more pallid earlier versions.

Twain also left a few parenthetical notes that capture the joy of his writing. For example, at one point Twain has trouble phrasing two lines from a poem about a dog eating the food left on the table for his sick master. He comes up with this:

“The dog’s his heir, and this estate

“That dog inherits, and will ate. (Note 1)”

The footnote has everything I like about Mark Twain’s writing.

“(Note 1) My child, never use an expression like that. It is utterly unprincipled and outrageous to say ate when you mean eat, and you must never do it except when crowded for a rhyme. As you grow up you will find that poetry is a sandy road to travel, and the only way to pull through at all is to lay your grammar down and take hold with both hands.”

You can find one of the English versions of Slovenly Peter online in its entirety here at Project Gutenberg. Read it to your children. See if it makes them laugh.