Douglas Adams tells this story in his classic novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy.

After waging frightful war against each other for centuries, two alien civilizations realized that the Earth was actually the source of the dreadful insult that had started the conflict. The strange and warlike beings sought vengeance by uniting and launching a million fierce star cruisers on a joint attack against Earth.

“For thousands of years, the mighty ships tore across the empty wastes of space and finally dived screaming on the Earth – where due to a terrible miscalculation of scale the entire battle fleet was accidentally swallowed by a small dog.”

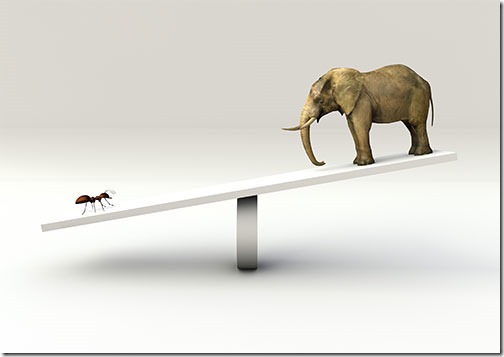

We have to guard against miscalculations of scale.

We all have a natural tendency to generalize from our own experiences, and to believe that problems can be isolated and solved if we just put enough people on the job. It is hard for us to understand the scale of our modern world.

I want to pull a single number out of a report that Facebook put together recently to help make a point about the difficulty of solving problems at scale.

The number is seven million.

In the last quarter of 2017, Facebook identified and deleted seven million fake accounts.

Try and get a handle on what it means to find seven million fake accounts. It is commonplace to complain that the big tech companies let mere algorithms determine which accounts to delete, or which posts to flag, or which ads to remove. How many employees would it take to identify seven million fake accounts in three months? The scale is hard to imagine.

Seven million is a really large number. How about the usual analogy? Seven thousand minutes is about five days. Seven million minutes is more than thirteen years.

We are currently obsessed with Russians who created fake accounts to influence the 2016 US election, but that’s just one example of a much bigger problem. The number of groups that try to game Facebook’s system to create fake accounts is staggering.

For a few dollars, anyone can purchase a fake Facebook account created with care. It includes a photo, name, email address, phone number, all the indicators of a real person, perhaps even a few hundred followers. Celebrities, politicians, and companies buy these accounts by the thousands to create the illusion of popularity or to launch a new product.

Individuals create fake accounts for cyber-bullying or to spread rumors.

Scammers, troll farms, and bogus businesses use automated scripts to create fake accounts by the score to solicit money or engage in online harassment.

Governments like Russia might sponsor the creation of fake accounts to affect the politics of the United States – or the Ukraine or France.

Not all fake accounts are created for improper reasons! People in countries with authoritarian governments might create fake accounts to conceal their identities and use Facebook to facilitate communication and broadcast truth about the regimes.

Mark Zuckerberg was brought before Congress to talk about Russia’s use of Facebook to influence the 2016 election. At some point Congress might try to draft legislation requiring Facebook to be more vigilant about detecting fake accounts, based on the misapprehension that Facebook just needs to hire enough people to examine each account and kick out the phonies.

It can’t be done that way. As a society we need to understand that.

You see, I fibbed a bit up above. We still haven’t gotten the scale right.

In the last quarter of 2017, Facebook identified and deleted seven million fake accounts . . . every day.

Actually it’s a bit more than that. Facebook disabled 694 million accounts in Q4 2017, which averages out to about 7.5 million accounts every day. The number dropped slightly in the first quarter of 2017, when Facebook deleted 583 million accounts, or about 6.5 million accounts every day.

When you find yourself thinking, well, somebody at Facebook should have noticed the fake Russian accounts in 2016 . . . you’re misunderstanding the scale of the problem.

When Senator Al Franken attacked Facebook because no one drew any conclusions about Russian involvement with election ads paid for in rubles . . . he was misunderstanding the scale of the problem. Chances are that ads arguably relating to American politics were also paid for in pounds, rupees, euros, pesos, krone, riyal, dinar, yen, yuan, and dirham. Facebook runs a global advertising business at the same unimaginably large scale.

I constantly hear journalists and pundits and normal people dismiss Facebook because their own personal use of it is not important to them. Roughly, their argument is: “Facebook has an influence on people’s opinions that I don’t agree with, and personally I don’t care about pictures of other people’s pets . . . therefore Facebook should be shut down.” Again, it’s a misunderstanding of the incredible variety of ways people use a global communications platform. Facebook has two billion separate active users every month. It is used for journalism all over the world, including its role as a source of news in countries that might not otherwise have any independent reporting. Millions of businesses depend on Facebook, including its crucial role for small businesses with limited advertising budgets. Its role in communications and social relationships extends to people who aren’t like you and might need that channel to trade information about life in an authoritarian regime, or to get support during a gender change, or for female entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia to sell products, or for farmers in Kuwait to sell sheep, or for people in India to let family members know they are safe.

If you discover a fake Facebook account, it is tempting to believe that you should report it to someone on the phone at the Facebook Fake Account Department. You’re misunderstanding the scale of the problem. Facebook’s algorithms are deleting seven million accounts every day. Human beings literally cannot have more than an insignificant role in that process, no matter how many employees Facebook hires.

For the same reason, law enforcement authorities are not going to follow up on the malicious spam message you got today. Google is not going to have an employee take notes on the phone about the inappropriate YouTube video you found. Again, you’re looking at a tiny bit of a problem that exists at an incomprehensible scale.

For better or worse, the world is operating at a scale that requires the tech companies to develop algorithms to help us communicate fairly and deal with each other honestly. It’s possible to imagine legislation that might assist that process but it will only make sense if we make an effort to understand the scale of the problems. Be wary of anyone who claims that our problems can be solved by if these companies would just hire enough people to (read the posts) (watch the videos) (check the companies behind the ads) (research the news). It’s a big, complicated, nuanced world.