Your personal information is being bought and sold by companies that lurk in the shadows. You’ve never heard of them. That’s the way they like it.

This is the most important issue that affects your privacy today.

Let’s start with a tight focus.

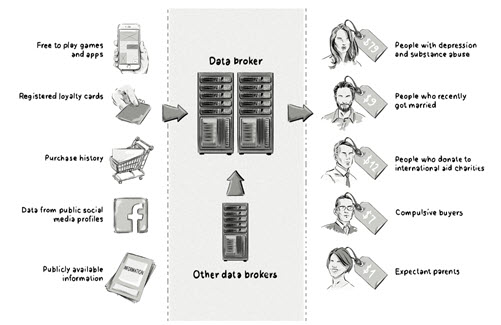

Assume there’s a company that methodically scrapes information from public records – drivers licenses, voter registration, property rolls, census and change of address records, birth certificates, marriage licenses, bankruptcy records. It combines that information with everything it can collect from social media sites or buy from private sources – bank card issuers and financial institutions, retailers, health care and insurance providers, whatever is available.

The company accumulates and distills that information into individual profiles, and keeps adding to each profile as more information comes in. It’s got your name and address. It’s got your email addresses and your phone number. Oh, and a few other things – these are just examples of the thousands of data points in an individual profile:

“Age, race, gender, height, weight, marital status, religious affiliation, political affiliation, occupation, household income, net worth, home ownership status, investment habits, product preferences and health-related interests.”

Now imagine that the company sells everything in the profile, all of that personal info about you, to an advertising company that uses it to target you with spam email and ads on websites.

That’s just nasty, right?

What is that company? Who gave it the right to invade your privacy and gather all that information?

Well, take a look at Experian and Equifax. The credit monitoring companies collect data about virtually every human being in the U.S., continually updated with info supplied by banks, mortgage companies, and retailers. And I’ll be darned, each of the credit monitoring agencies also has a separate division that packages that personal information and sells or licenses it to other companies for targeted advertising and marketing. That’s why it was such a big deal when Equifax was hacked in 2017 – it has a lot of information about a lot of people.

At least credit monitoring agencies have a plausible business reason to accumulate all that data, and there is some minor regulation of the information they are allowed to disclose to others.

But they’re not the only ones. There’s also Acxiom, which arguably has more personal information about more people than any other company in the world. (Facebook and Google are in a different category – see below.) FastCompany estimates that in 2018 Acxiom had 10,000 data points on 2.5 billion consumers around the globe. Acxiom doesn’t have another business. It has become a multi-billion dollar company just by trading in data – your data, the details of your life, bought and sold all day, every day.

Okay, we’ve got Experian, Equifax, and Acxiom – three companies sucking up data from every possible source and compiling it into profiles that marketers can use to send you spam.

Data brokers – the shadow economy

It’s time to pull out. Zoom back so you can get a broader view of the U.S. economy.

There aren’t just three companies collecting and selling personal data. There are more than 4,000 companies in the business of compiling personal information into profiles that are sold to advertisers and marketers.

The data broker industry is estimated to be worth at least $200 billion.

Data brokers are unregistered, unregulated, and untracked.

You cannot find out what data a broker holds on you, how a broker got it, or how it is used.

Many of the data brokers are enormous companies with billions of dollars in annual revenue, but you’ve never heard of them. They are thriving in the shadows.

FastCompany: “They include big names in people search, like Spokeo, ZoomInfo, White Pages, PeopleSmart, Intelius, PeopleFinders, and the numerous other websites they operate; credit reporting, like Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion; and advertising and marketing, like Acxiom, Oracle, Innovis, and KBM.”

Some data brokers offer fraud detection, used by banks to evaluate loan applicants and by phone carriers to check your bona fides.

Some data brokers sell profiles that are used for risk mitigation by other businesses. If you have an active gym membership, a life insurance company might decide you have a lower risk of having a heart attack, and offer you lower premiums.

All too often, there are examples of companies using personal data to evade laws that limit predatory and discriminatory practices. The most notorious incident was reported by Forbes six years ago – a data broker was selling lists of rape victims, alcoholics, and “erectile dysfunction sufferers.”

“Lists reveal information that would surprise most people. Data brokers sell lists of people suffering from mental health diseases, cancer, HIV/AIDS, and hundreds of other illnesses,” said Pam Dixon, executive director of the World Privacy Forum. “Data brokers sell lists of people who live in or near trailer parks so that these undesirable consumers can be targeted for suppression. Data brokers sell lists of people who are late on payments, often to those who make predatory offers to those in financial trouble. Data brokers sell lists of people who are impulse buyers or ‘eager senior buyers.’ All in all, there are millions of lists.”

Data brokers often sell profiles to government agencies, like the FBI, allowing law enforcement agencies to circumvent laws that protect privacy. Other abuses of personal data are easy to imagine. For example, the Washington Post says: “A list of people who have Alzheimer’s disease could be purchased by bad actors who want to take advantage of mentally ill people. . . . Free websites that give anyone easy access to people’s current home addresses can be valuable tools for stalkers and abusers who are trying to locate their victims.”

Will regulation help control the data broker industry?

In early 2019, Vermont became the first state to attempt any regulation of the data broker industry. Vermont’s law requires data brokers to register with the state and live with four governing principles: transparency, duty to secure data, no fraudulent collection, and free credit freezes.

That’s great! Although it’s, well, only Vermont, so most data brokers have ignored the registration requirement, and it doesn’t seem like the industry has put on the brakes.

In October, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed sweeping privacy safeguards that will take effect next month. Among other things, the law gives consumers the right to know what information businesses are collecting about them and why they’re collecting it. Regulation in California is important and influential; if California’s law is effective, other state legislatures may move forward with measures to give residents more control over their data.

You may see tech companies and even data broker companies urging the federal government to set up federal privacy regulations. Be afraid! The industry is gearing up to resist the California law and any other state laws with every weapon in their arsenal. If regulation is inevitable, the industry will push for a weaker federal law that preempts state laws. A recent New York Times Op-Ed article by the chief data ethics officer for Acxiom makes a pitch for a federal data registry to protect “consumer privacy on the one hand, while supporting the inventive, valuable and responsible uses of data on the other.” It is literally a magic trick where you are supposed to watch one hand and ignore what the other hand is doing.

What about Facebook and Google?

We’ve been talking about so-called third-party data brokers that collect and sell personal information from consumers with whom the broker has no direct relationship. Facebook and Google are first-party data miners; they collect information directly from you when you interact with their services. Similarly, retailers like WalMart and Target get much of their data from observing your shopping habits.

Google has more personal information about you than any other company. It studies your browsing habits; it follows you continuously as you use Google Maps or an Android phone; and it analyzes your photos. Google does not let anyone else see the data. It does not sell or license the data to third parties. Google allows advertisers to specify who they’re trying to reach; then Google analyzes its data and places ads where they fit. Google has a terrifying amount of data about us and could tear us apart if it turns evil. But for now, Google keeps your data to itself. I don’t consider that to be an invasion of privacy.

Facebook also accumulates mountains of information about you, both by watching you use Facebook and by sucking up data from third parties. Unlike Google, though, Facebook initially shared personally identifiable information with everyone from app makers to “researchers” like Cambridge Analytica. Facebook claims to have reformed, and piously declares that it does not sell data. As recently as a year ago, though, the New York Times concluded:

“While it is true that Facebook hasn’t sold users’ data, for years it has struck deals to share the information with dozens of Silicon Valley companies. These partners were given more intrusive access to user data than Facebook has ever disclosed. In turn, the deals helped Facebook bring in new users, encourage them to use the social network more often, and drive up advertising revenue.”

The increasing scrutiny and threat of regulation may have led Facebook to be more careful this year about not sharing personal data. Technically it’s not a member of the shadow data broker industry. Paradoxically, though, Facebook’s privacy breaches and public relations blunders may be important reasons that the data broker industry winds up more tightly regulated.

Is there anything you can do?

Not really. The companies operate independently; maybe someday there will be regulation and unambiguous rules, but today it is effectively impossible to see the data that has been collected, much less to remove it. Anyone who has tried to get a credit agency to correct a mistake knows it is virtually impossible – and that’s just one or two companies out of several thousand. (Here’s an instructive story from Forbes about one man’s mostly futile attempt to discover how his name was added to an AARP mailing list.)

Once information about you has been packaged and sold and resold – and it has been – it lives indefinitely in the giant servers run by the data broker industry. If it is hacked – and it has been – then your profile joins the billions of other profiles being traded on the dark web.

(Update 10/19/2020: If you are interested in learning more about the dark web, this is a fascinating collection of information: Everything You Need To Know About The Dark Web In 2020.)

Privacy? It’s not happening, I’m afraid. You won’t see the companies operating in the shadows, but don’t forget they’re there – and they’re watching you.

Experian and Equifax also operate in Australia and are entrenched in our financial systems. They provide us with free credit scores (which we can legally request each year). Thanks Bruce for shining a light on the ‘industry’.