The phone rings. It’s a scammer. “I’m calling from Microsoft about a problem with your computer.” “I’m calling from the IRS to discuss your past-due tax bill.” “Would you like to contribute to the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation?”

Don’t sympathize with the person on the other end – they are criminal scum trying to steal from you. Hang up. Go ahead, be angry. They deserve it.

But don’t imagine that they have chosen an easy life or that they are living high on ill-gotten proceeds.

You’re probably talking to someone working in a crowded cubicle at a call center. The salary is below market but a job is a job when nobody is hiring, and there are occasional bonuses and free lunches. They spent a week memorizing scripts and going through training. When they arrive at work and log in, calls start flooding in; the days are spent repeating the scripts nonstop, trying to fool people, dealing with hangups and abuse.

There’s no glamor in cybercrime.

Here’s an anonymous Quora story about an Indian call center. “You repeat same script on each call. Fake name followed by you have a virus, then screenshare, show him stuff like registry, dumps etc and scare them. Then sell them the plans for 300, 600 dollars or some one time fix. These people charge money and literally do NOTHING! They sell you air.”

Entry-level callers are paid far less than the amounts they’re extorting from victims. Reuters talked to an economics graduate who worked in an Indian call center because “it was a job and people aren’t hiring.” For every dollar brought in, callers were given the equivalent of three U.S. cents.

The lives of other types of high-tech criminals are just as unexciting. Most of the hackers running botnets or distributing ransomware or trying to penetrate large companies are doing work that is mind-numbingly boring and tedious.

Forget about the hackers in movies, quickly tapping in commands to break into the Pentagon or unlock the database with the bank account numbers. Think instead about administrative work and maintenance, trying to keep up with tickets in the customer support system, and dealing with billing issues.

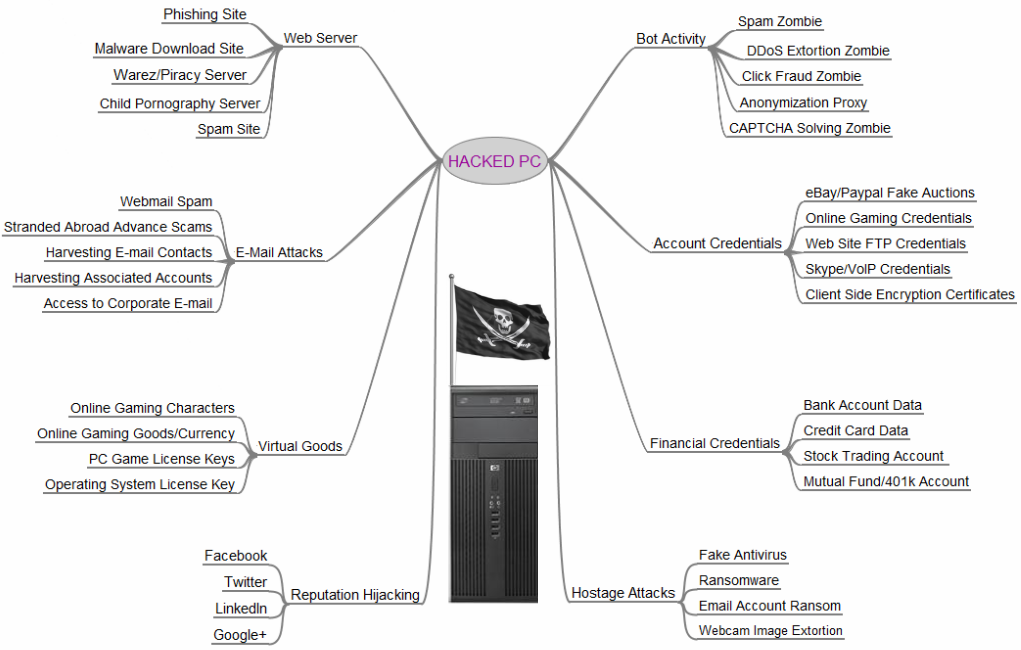

Security researcher Brian Krebs created the picture above to show the variety of ways that a bad guy can monetize your hacked PC.

“One of the ideas I tried to get across with this image is that nearly every aspect of a hacked computer and a user’s online life can be and has been commoditized. If it has value and can be resold, you can be sure there is a service or product offered in the cybercriminal underground to monetize it.”

There are many types of hackers, from individuals to employees of Russian and Chinese state agencies. More and more, though, cybercrime is dominated by large business organizations with traditional business structures:

“Cybercriminal organizations aren’t all the same, but a typical structure looks like this: a leader, like a CEO, oversees the broader goals of the organization. He or she helps hire and lead a series of “project managers,” who execute different parts of each cyberattack. . . .

“Specialists in malicious software might start by buying or tweaking a custom product to steal the exact kind of information the group requires. Another specialist might work to send fraudulent emails to deliver the malicious software to targeted companies. Once the software is successfully delivered, a third specialist might work to expand the group’s access within the targeted corporation, and seek the specific information the group hopes to sell on the black market.”

Much of the work is mundane and dull. A recent paper from Cambridge University’s Cybercrime Center discusses the low-income and low-skilled manual administrative work required to keep cybercrime infrastructure running. Media coverage of “sophisticated” attacks and massive payouts is frequently incorrect and counterproductive if it encourages people to turn to cybercrime. From the report:

“While they may sound glamorous, providing these cybercrime services require the same levels of boring, routine work as is needed for many non-criminal enterprises, such as system administration, design, maintenance, customer service, patching, bug-fixing, account-keeping, responding to sales queries, and so on.”

The businesses making money from today’s cybercrime are frequently the ones selling the malware or managing cybercrime services for hire. (Think about the old saying that the people who got rich in the gold rush were selling the shovels to the gold miners.) Krebs says the cybercrime services “tend to live or die by their reputation for uptime, effectiveness, treating customers fairly, and for quickly responding to inquiries or concerns from users. As a result, these services typically require substantial investment in staff needed for customer support work (through a ticketing system or a realtime chat service) when issues arise with payments or with clueless customers failing to understand how to use the service.”

There are criminal marketplaces that operate in a similar way to eBay, with ratings and reviews for the malware, botnets, spam attacks, denial of service attacks, and the rest. There are escrows for holding money until everything is checked out. Arbitration is available for disputes. It’s roughly like any other traditional business – or, from a different perspective, like the way organized crime has operated for decades.

There are inspired hackers out there (most likely working for governments). There are cybercriminals getting rich. But the hacker with the hoodie has mostly been replaced by low-paid drones doing tedious work. If you’re a guidance counselor, advise your students to consider a career in cybersecurity instead – if they’re going to spend their days troubleshooting network and security problems, it might as well be for the good guys.