The longest mudslide in history was just reported by an international team of researchers. Huge quantities of sand and mud traveled nearly 750 miles, causing significant damage along the way.

You didn’t miss it in the news. It didn’t get much notice because the mudslide was underneath the ocean. A major river flood coincided with unusually high spring tides, causing an avalanche of sand and mud to flow from the mouth of the Congo River into the Congo Submarine Canyon at depths of up to 15,000 feet.

We don’t know much about undersea mudslides – they’re unpredictable and hard to measure. This one was able to be tracked because the Congo Submarine Canyon carries undersea cables for Internet traffic and the flood broke two of them. As it happened, there were lots of sensors recording data about the cables and researchers were able to reconstruct what happened, although it took a while to crunch the data – the mudslide was in March 2020 and the report was just released last month. According to observations by Professor Talling and the team, “the data that we recovered from the seabed sensor and mooring data sets within the Congo Canyon have revealed that the undersea mudslide is possibly the longest recorded sediment flow yet measured in action on our planet.”

The mudslide is cool but today let’s talk about those broken undersea cables. Come on, give me ten minutes – it’s a crucial part of the world that you’ve never thought about and it’s interesting to know it exists, plus there’s a cool story about fake news back in the 1800s.

Your friend the undersea cable

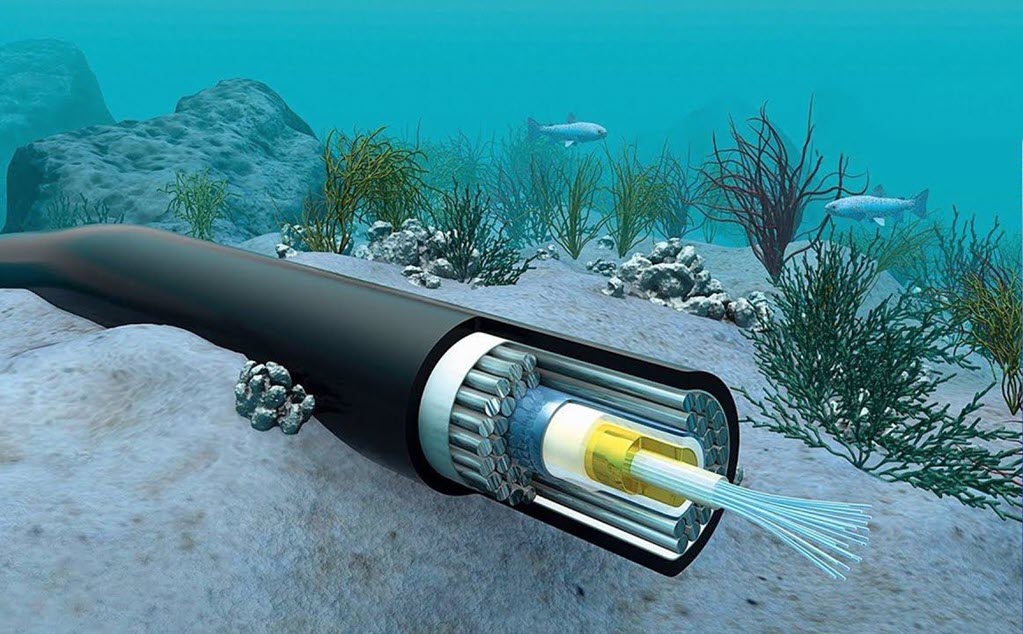

The Internet runs over wires carrying little dit-dahs of electricity. Or cables with beamsicles of light bouncing around, whatever, the point is that the hard work of running the Internet does not happen over the air. You have a wifi connection in your home or office but a cable brings the Internet to your building. Your phone gets an Internet connection from a nearby cell phone tower but sure enough there are cables leading to each tower.

Now let’s step back. Grab a globe and take a look at it.

Okay, you don’t have a globe, nobody has a globe any more. But you know the basics, right, the earth is round, continents separated by big oceans? Think about clicking on a link to a website in England or China or Japan. It gets to your computer or phone over a wire. More than 99% of all data traffic between continents travels over undersea cables, including trillions of dollars of daily money transfers. Satellites are used for redundancy and backup but today’s Internet depends on really, really long extension cords.

There are only 380 undersea cables today for the entire world. Not very many, eh? As recently as 2012 the US was more or less cut off from Europe for several hours after Hurricane Sandy because all the Atlantic cables came onshore in New York and New Jersey and the landing stations were knocked out by the storm. New cables since then have been spread out along the east coast. Today most places have at least some redundancy. The broken cables off the coast of Congo in 2020 caused some difficulty for African ISPs and telcos but the continent did not go offline. But there are many places in the world that do not have reliable connections or sufficient bandwidth through the existing cables.

And that’s a problem because undersea cables are expensive and finicky. A new cable costs hundreds of millions of dollars, and they break all the time – there are underwater earthquakes or mudslides or the cables get snagged in fishing nets and anchors. There is a large industry devoted to cable repairs.

In the last ten years Google and Facebook have become the biggest investors in new undersea cables. Facebook is heavily involved in the 2Africa project to encircle the entire African continent with new cables, and announced a new project earlier this week to build a fiber network serving 30 million people across Central Africa. Google is the sole owner of five undersea cables around the world and a part owner of eleven more, with a new transatlantic cable that came online in February and another one that will be completed next year. The newest cables have staggering data capacities – Google’s new transatlantic Dunant cable delivers 250 terabits per second across the Atlantic.

It’s kind of an exciting engineering project. Imagine a 4,000 mile long garden hose that weighs ten million pounds. It can take a month just to load the cable onto the specialized ship that will take it across the ocean along routes that are preferably flat and deep and geologically stable. Undersea cables are occasionally cut by pirates, tapped by spies, and lately, gasp, built by Huawei, which causes suspicion in some circles. Pretty cool, eh?

The first transatlantic cable

“But wait,” I hear you cry. “How did it start? Are there any good stories about the first transatlantic cable?”

I’m glad you asked. Let me tell you about the very first cable in 1858.

It was a dark and stormy night.

Experiments with undersea cables over short distances had been going on for several years, starting in 1850. Cables were unreliable and broke frequently, ships were near foundering or being driven into rocks by inclement weather, it was a difficult business.

Finally, though, a test expedition in 1857 went reasonably well, leading to the funding of the first serious effort to lay a transatlantic cable in 1858. Fun fact: Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph, was on board one of the 1857 ships but didn’t actually do anything because he was seasick the entire time.

The first 1858 expedition was broken up by a fierce week-long Atlantic storm that nearly sank the two cable-laying ships, one from the UK, one from the US. According to journals kept on board:

Amid loud shouts and efforts to save themselves, a confused mass of sailors, boys, and marines with deck buckets, ropes, ladders, and every, thing that could get loose, and which had fallen back to the port side were being hurled again in a mass across the ship to starboard. Dimly, and for a moment, could this be seen; and then, with a tremendous crash, as the ship fell over still deeper, the coals stowed on the main deck broke loose, and, smashing everything before them, went over among the rest to leeward. The coal dust hid everything on the main deck in an instant; but the crashing could still be heard going on in all directions, as the lumps and sacks of coal, with stanchions, ladders, and mess tins, went leaping about the decks, pouring down the hatchways, and crashing through the glass skylights into the engine room below.

The ships survived the storm but the expedition failed after constant cable breakages, the loss of 40 miles of cable when it slipped irretrievably away into the depths, fog that threatened to have the two ships running into each other, and “beef which had been kept three years beyond its warranty for soundness.”

The second expedition a month later went more smoothly, with thrilling nautical adventures but nothing as dire as the first trip. The cable was landed at both ends and on August 13, 1858, the first telegraph message was sent between the US and the UK:

Europe and America are united by telegraphy. Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, goodwill towards men.

A short message was then transmitted by Queen Victoria congratulating President Buchanan on the “successful completion of this great international work.” Messages on the new cable were sent with Morse code. The Queen’s 98-word message took 16 hours to send.

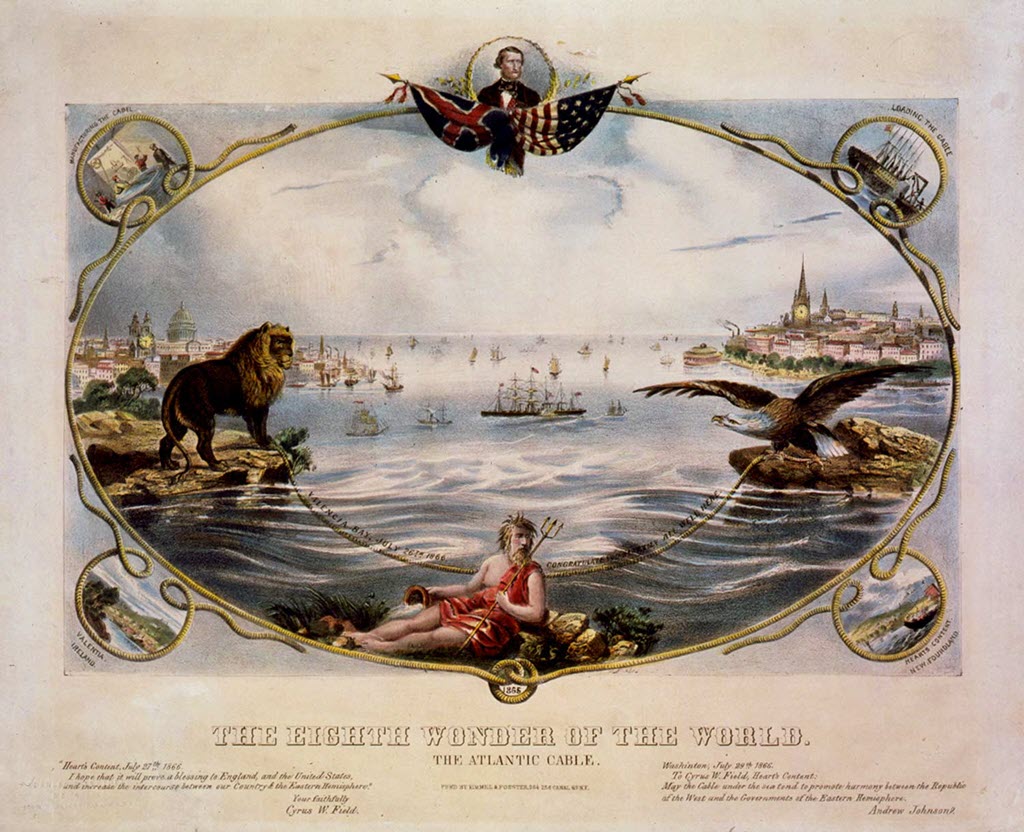

There was much rejoicing. “A grand salute of 100 guns resounded in New York City, the streets were decorated with flags, the bells of the churches were rung, and at night the city was illuminated. There was a parade, followed by an evening torchlight procession and fireworks display, which caused a fire in the Town Hall.” Broadsides were printed up for the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

Behind the scenes, though, there was a bit of shenanigans. Two strong personalities had been clashing over the design of the cable and the equipment for detecting the telegraph signal. Wildman Whitehouse was a medical doctor by training whose enthusiasm for the new electrical technology led him to give up his career and became one of the project’s chief electricians despite having no training. He thought the best way to get a signal from England to the US was to turn up the dial to eleven, using massive high-voltage.

Another senior member, William Thomson, invented a sensitive new instrument that used low voltage to detect the Morse code dots and dashes. Smart guy. Should have been in charge.

When the cable was completed, Whitehouse hooked up his high voltage equipment and promptly blew out the cable. The Queen’s message made it one way but successful transmission required a return receipt and Whitehouse couldn’t read the receipt.

So Whitehouse secretly hooked up his competitor’s new invention, got the receipt, and manually typed it into his own equipment so it would look like it came from his printer. He told the press the Queen’s message had been received and the world went nuts.

Thanks in part to Whitehouse’s fun with high voltage, the cable failed completely three weeks later. It handled a grand total of seven hundred messages – very, very slowly – over its entire lifespan.

And that was the end of the first transatlantic cable. The next cable wasn’t laid until 1865. By the end of the 19th century, there were a dozen or more cables in the Atlantic Ocean, and the speed, oh, the raw speed – almost 120 words per minute. Whoosh!

Great stuff. Add an undersea cable landing point to your next seaside vacation. It might not be very interesting to look at but it means a lot to the system that keeps our world going.