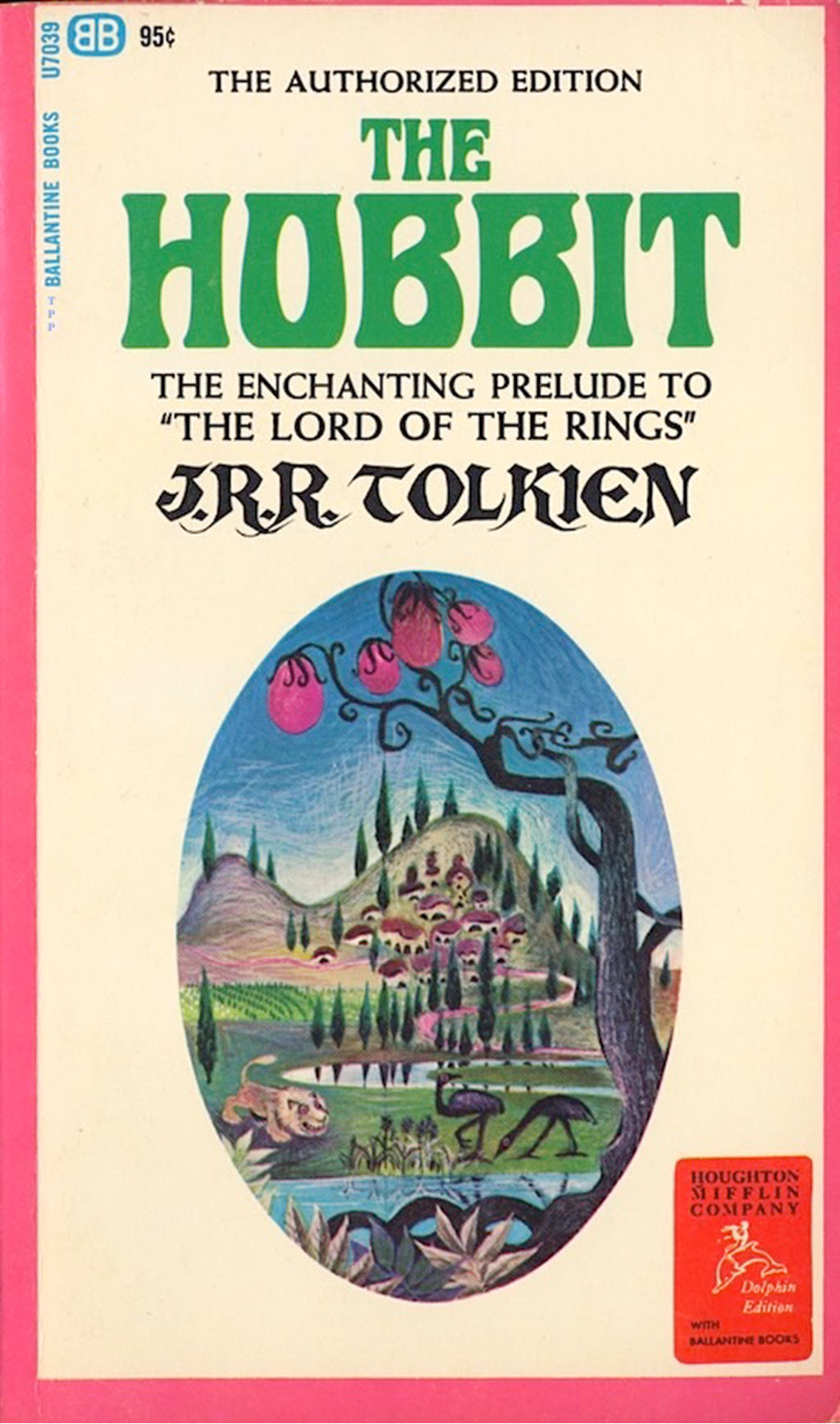

The painting on the cover of the first US paperback edition of The Hobbit has a lion, a fruit tree, and a pair of emus.

There are no lions in The Hobbit. There are no fruit trees or emus.

J.R.R. Tolkien was baffled. He wrote to the publisher, “Where is this place? Why emus? And what is the thing in the foreground with pink bulbs?

The lion was removed. The emus remained for many years. The artwork became iconic.

It happened because the publisher was in a hurry - and therein lies a tale.

This story is not new; you might even remember it if you grew up in the US in the 1960s.

But it’s a great story about publishing and piracy and what the world was like before The Lord Of The Rings exploded into global popularity.

The beginning

The first edition of The Hobbit was published in 1937. It was well reviewed and the hardcover editions sold respectably for the next fifteen years.

Tolkien worked steadily on The Lord Of The Rings but he was a perfectionist and years went by while he wrote and rewrote his manuscript, revising scenes and reconsidering every tiny detail. Plus he had a day job as an Oxford professor and there was a war going on. He more or less finished his work in 1949, then more years went by before the books appeared in print.

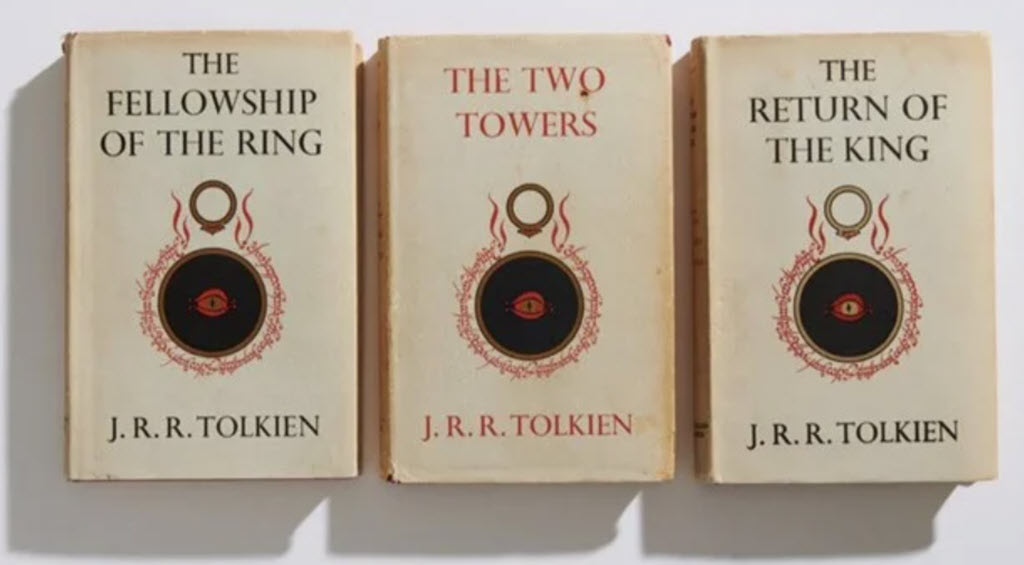

The UK publisher, George Allen & Unwin, pushed Tolkien to allow the book to be split into three volumes. He grudgingly accepted out of fear that the books might not otherwise ever see print. They were published several months apart in 1954 and 1955.

In the US, Houghton Mifflin wasn’t positive about the sales appeal of the lengthy trilogy. Instead of incurring the expense of setting the book in print on US printing presses, Houghton Mifflin had George Allen & Unwin ship over page blocks with the entire text of the UK edition. Houghton Mifflin bound the pages printed in the UK, substituting a few pages at the beginning with US copyright and publishing information. The rebound George Allen & Unwin books were released as the US hardcovers shortly after the UK books were published.

Remember the page blocks from England. They’re part of the story.

The books were well received. Sales of the hardcovers steadily increased through the 1950s in the UK and the US. Literary figures praised the trilogy - W. H. Auden, Iris Murdoch, C. S. Lewis. The series won the International Fantasy Award in 1957.

The book publishing industry is smaller than you think. The Lord Of The Rings hardcovers sold respectably but they were not blockbusters. The UK and US publishers sold tens of thousands of copies of the Lord Of The Rings volumes in the next ten years after their 1955 publication.

In 1965, The Hobbit had been in print for nearly 30 years. The Lord Of The Rings trilogy had been on the market for a full ten years.

That was the year everything changed.

Ace paperbacks

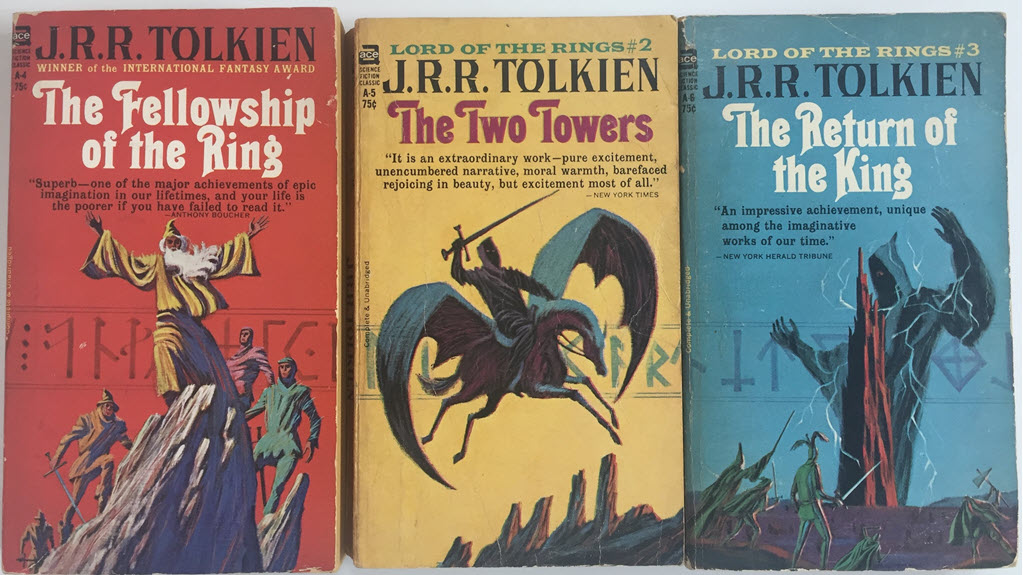

Donald A. Wollheim was a pioneering American science fiction editor, publisher, and writer. He was one of the founders of modern science fiction publishing, and helped launch the science fiction paperback market as editor-in-chief of Avon Books and most notably Ace Books in the 1950s and 1960s.

Wollheim called Tolkien in 1964 to inquire about publishing paperback editions of The Lord Of The Rings. The call did not go well. Tolkien did not think his books were mass market and he told Wollheim that he would never allow his great works to appear in so ‘degenerate a form’ as the paperback book.

Wollheim was stubborn. He found a loophole.

Copyright law was different in the 1960s. Because the US hardcovers had been bound using pages printed in the UK, they were not covered by US copyright law. Houghton Mifflin had failed to properly copyright the books and later mishandled a renewal.

Technically The Lord Of The Rings was in the public domain in the US. Donald Wollheim was the first person to realize it.

In May of 1965, Ace Books published an unauthorized paperback version of The Fellowship Of The Ring, following with The Two Towers and The Return Of The King in July. It was the first time the books had been available in paperback anywhere in the world. They were priced cheaply, at 75 cents each. Ace did not pay royalties.

They sold like crazy.

And Tolkien went ballistic.

He started working on revisions, which would allow the copyright to be renewed. In the next few months he revised the appendices, expanded the prologue, and revised the Foreword.

But he also mobilized readers. He wrote letters to fan clubs, lobbied against the pirated editions in interviews, issued press statements. The fuss made its way to mainstream newspapers.

The high-profile dispute drew massive attention to The Lord Of The Rings, which drove sales of the Ace paperbacks. In a few months Ace sold 100,000 copies of the trilogy.

Ballantine paperbacks

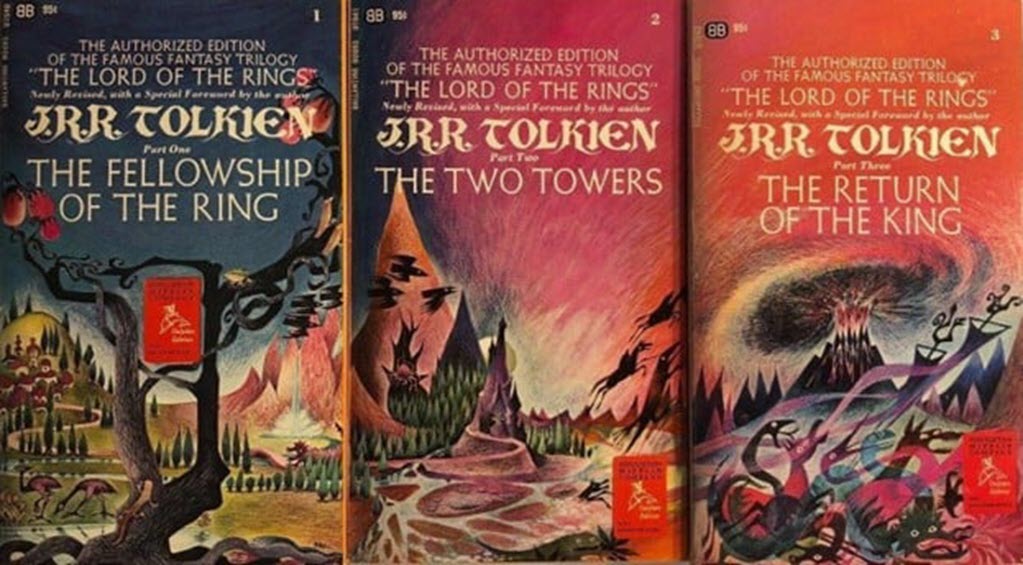

Meanwhile Ballantine Books was racing to put together a deal with Tolkien and get new paperbacks on the market. The Ballantine paperbacks appeared in November 1965, barely six months after the Ace paperbacks.

That’s why the Ballantine editions announce proudly that they are the “Authorized Edition” of The Lord Of The Rings, “newly revised, with a special foreword by the author.”

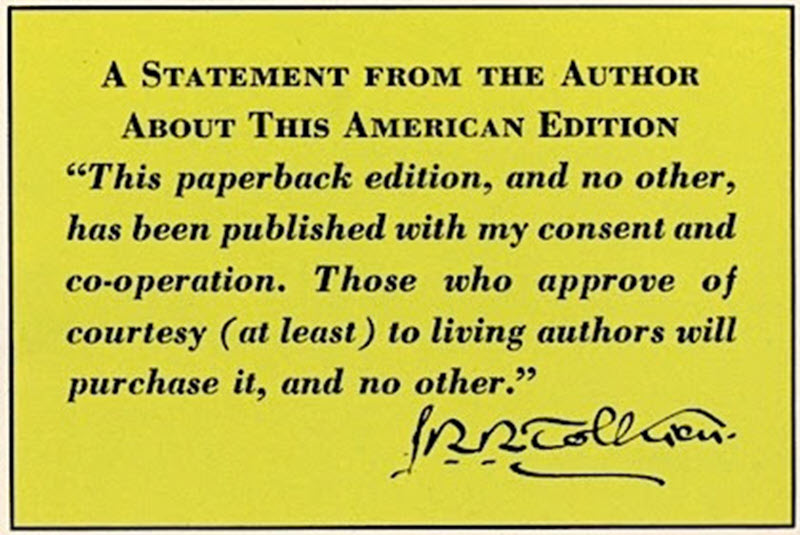

Each volume also has the above statement on the back cover: “”This paperback edition, and no other, has been published with my consent and cooperation. Those who approve of courtesy (at least) to living authors will purchase it, and no other.”

Ballantine hired an artist to illustrate the covers. Barbara Remington was given a vague description of the books by the Ballantine editor but she didn’t have a chance to read the books before her deadline. She was forced to embellish and work from her imagination. There was no time! The Hobbit was published in August 1965; the three LOTR volumes appeared three months later.

The lion, the emus, the fruit tree - that’s an artist doing the best she can without enough information.

Her painting of Middle Earth, designed as a triptych to be sectioned off as the cover art, became iconic. It was turned into a poster that decorated hundreds of thousands of dorm rooms, and the style influenced fantasy art for decades to come.

A few months later, in February 1966, Ace Books stepped back. They agreed not to print more copies of their books and delivered all of their profits to Tolkien, a grand total of nine thousand dollars.

The Tolkien boom

Within ten months, Ballantine had sold a quarter of a million copies of the authorized paperbacks. The Lord Of The Rings books became ubiquitous on college campuses and were a touchstone for 1960s counterculture and hippies, who found resonance with the themes of anti-industrialism and individual freedom.

The Lord Of The Rings consistently ranked among the top-selling books worldwide through the 1970s and into the 1980s. Catchphrases and references crossed over into popular culture. Organized fandom appeared everywhere - clubs, academic societies, newsletters, fan conventions, the first movie and animated adaptations.

By 1985 more than 50 million copies of the books had been sold. The boom continued for fifteen more years until the first Peter Jackson film, The Fellowship Of The Ring, appeared in 2001, igniting a new wave of LOTR mania that shows no signs of slowing down.

And it all began with a baffling cover, a legal loophole, and an author’s indignant protests, launching a publishing phenomenon and transforming The Lord Of The Rings into a cultural touchstone.