Today’s sermon concerns Cormac McCarthy, our greatest living author. McCarthy is extraordinarily reclusive; he lives in New Mexico, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, and he has given one and only one interview during his long career. He doesn’t do book tours or signings or appear on podcasts or tweet or provide blurbs for other authors. His literary reputation is unparalleled but he’s not a celebrity because he deliberately shuns the high public profile that we expect from best-selling authors.

McCarthy has written ten novels. None of the first five sold more than 5,000 copies in hardcover. He finally won widespread recognition when All The Pretty Horses won literary book awards in 1992, and his name became more widely known when Matt Damon and Penelope Cruz starred in the movie of that book in 2000.

McCarthy became even better known after the 2007 release of the Coen Brothers movie made from his novel No Country For Old Men. Remember the scene with Javier Bardem playing the dead-eyed killer Anton Chigurh, creating almost unbearable tension and dread by doing nothing more than asking a shopkeeper to call a coin heads or tails? That’s McCarthy. It’s in the novel.

The Road was released in 2006, McCarthy’s last published novel, an extended literary exercise in bleakness and shades of grey. It won a Pulitzer Prize and was quite a best-seller. It was made into a movie starring Viggo Mortensen which was well received but not seen by very many people because it was faithfully grey and bleak and would cause popcorn to seem dry and tasteless.

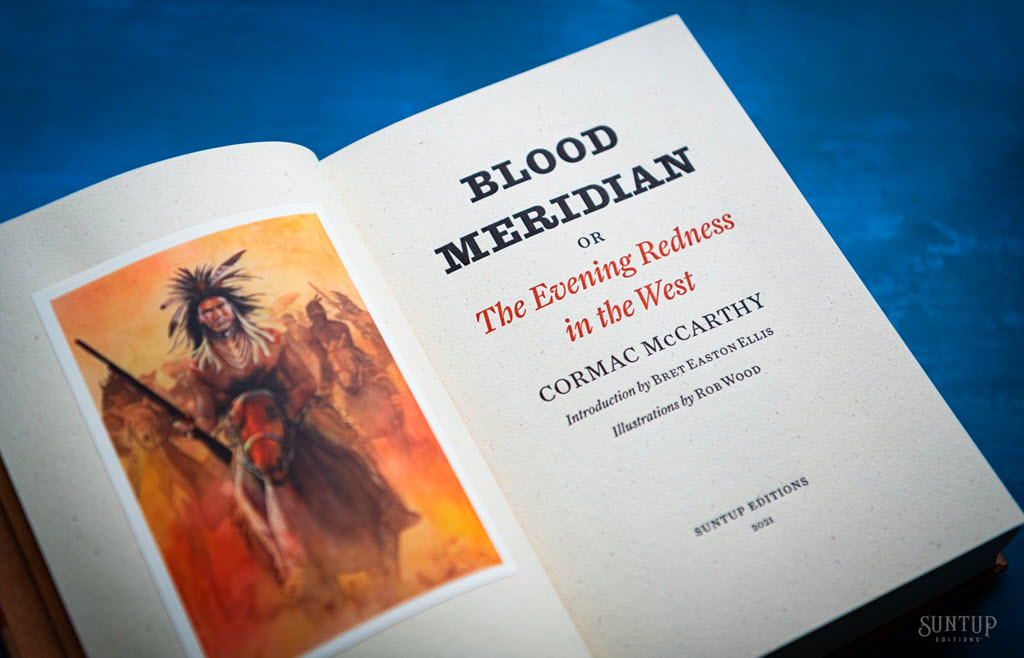

Blood Meridian

Before the acclaim and the best-sellers came Blood Meridian in 1985, widely recognized today as McCarthy’s magnum opus and one of the greatest American novels of all time. Critic Steven Shaviro wrote:

In the entire range of American literature, only Moby-Dick bears comparison to Blood Meridian. Both are epic in scope, cosmically resonant, obsessed with open space and with language, exploring vast uncharted distances with a fanatically patient minuteness. Both manifest a sublime visionary power that is matched only by still more ferocious irony. Both savagely explode the American dream of manifest destiny of racial domination and endless imperial expansion. But if anything, McCarthy writes with a yet more terrible clarity than does Melville.

Like most of McCarthy’s work, Blood Meridian is violent. It is nihilistic. It is bleak. It is a constellation of depravity and agony. Its world is all squalor and filth. It is difficult to read – McCarthy uses many unusual or archaic words, with no quotation marks for dialog and sparse punctuation with no semicolons.

It’s . . . well, perhaps you picked up on what I was subtly trying to convey. Blood Meridian is not for everyone.

But the words, the glorious, lyrical, epic words.

I want you to read one passage. It is luminous literary legerdemain and I do not know its equal. It condenses myth and history and violence. I am not alone in believing that the legion of horribles sentence – just one sentence! – is one of the greatest sentences in all of English literature.

A few of you will read this and understand the power and the glory of what McCarthy does and maybe you will read Blood Meridian and discover Cormac McCarthy and your life will be richer and you can thank me later.

Most of you – I mentioned that this isn’t for everyone, right? I don’t want you to feel bad if this doesn’t reach you and I don’t want you to think for a second about the sadness of your drab, wretched lives.

Blood Meridian is a Western, set in Texas and Mexico in the 1850s. Captain White’s unauthorized and sad “army” of irregulars rides through barren, hostile terrain where they are set upon by a war party of Comanche Indians concealed behind a herd of horses and cattle.

This is Blood Meridian. Ready?

The captain watched through the glass.

I suppose they’ve seen us, he said.

They’ve seen us.

How many riders do you make it?

A dozen maybe.

The captain tapped the instrument in his gloved hand.

They dont seem concerned, do they?

No sir. They dont.

The captain smiled grimly. We may see a little sport here before the day is out.

The first of the herd began to swing past them in a pall of yellow dust, rangy slatribbed cattle with horns that grew agoggle and no two alike and small thin mules coalblack that shouldered one another and reared their malletshaped heads above the backs of the others and then more cattle and finally the first of the herders riding up the outer side and keeping the stock between themselves and the mounted company. Behind them came a herd of several hundred ponies. The sergeant looked for Candelario. He kept backing along the ranks but he could not find him. He nudged his horse through the column and moved up the far side. The lattermost of the drovers were now coming through the dust and the captain was gesturing and shouting. The ponies had begun to veer off from the herd and the drovers were beating their way toward this armed company met with on the plain. Already you could see through the dust on the ponies’ hides the painted chevrons and the hands and rising suns and birds and fish of every device like the shade of old work through sizing on a canvas and now too you could hear above the pounding of the unshod hooves the piping of the quena, flutes made from human bones, and some among the company had begun to saw back on their mounts and some to mill in confusion when up from the offside of those ponies there rose a fabled horde of mounted lancers and archers bearing shields bedight with bits of broken mirrorglass that cast a thousand unpieced suns against the eyes of their enemies. A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners, coats of slain dragoons, frogged and braided cavalry jackets, one in a stovepipe hat and one with an umbrella and one in white stockings and a bloodstained weddingveil and some in headgear of cranefeathers or rawhide helmets that bore the horns of bull or buffalo and one in a pigeontailed coat worn backwards and otherwise naked and one in the armor of a Spanish conquistador, the breastplate and pauldrons deeply dented with old blows of mace or sabre done in another country by men whose very bones were dust and many with their braids spliced up with the hair of other beasts until they trailed upon the ground and their horses’ ears and tails worked with bits of brightly colored cloth and one whose horse’s whole head was painted crimson red and all the horsemen’s faces gaudy and grotesque with daubings like a company of mounted clowns, death hilarious, all howling in a barbarous tongue and riding down upon them like a horde from a hell more horrible yet than the brimstone land of Christian reckoning, screeching and yammering and clothed in smoke like those vaporous beings in regions beyond right knowing where the eye wanders and the lip jerks and drools.

Oh my god, said the sergeant.

I want to pull a phrase from there and hold it up to you and point until you acknowledge how perfect it is, how much it conveys in a few words – perhaps this one: “breastplate and pauldrons deeply dented with old blows of mace or sabre done in another country by men whose very bones were dust.” Then cast it aside and reach for another and another and another.

I would sacrifice to multitudes of gods to be a good enough author to someday, just once, be inspired to write a phrase as wonderful as “a company of mounted clowns, death hilarious.”

Oh my god indeed.

We’ll talk more about McCarthy’s books next time.

He is the Lord God Incarnite of language of speech of the sounds and utterances we use to tell our fellows about the world and how we apprehend it

Or ask the long one. He will say it better

Back in 2004, I was in my backyard (tanning) and I read this passage. I immediately jumped on the phone and read it to my Dad.

I’d never read anything like this. I started looking up some of the words and was amazed at how terrify the images were.

I tell friends how great the book is and then, at the same time, warn them, that I’m not recommending it.

Speechless what else can be said, written . . .